In response to stunning losses of wetlands and waterfowl in the early 1900s, a discussion arose in the 1920s concerning the possibility of creating a Federal Waterfowl Hunting license. This would be a stamp not unlike licenses that many states had used for years for hunting, with proceeds going to save wetland habitat. Through the 1920s, debates among conservationists, policy-makers, and hunters raged over how best to secure wetlands and waterfowl. Meanwhile, the resources degenerated, setting up conditions that would in the next decade be known as the Dust Bowl.

With the 69th Congress (1925-1927), Senator Peter Norbeck (R-SD) pushed a conservation bill, but it ultimately had the federal license portion removed. What eventually passed Congress—the Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929—did have a number of important elements (including creating a Migratory Bird Conservation Commission), but it had no reliable funding mechanism. (Only annual federal appropriations could sustain MBCC acquisition decisions.)

FDR soon appointed a Presidential “Committee on Wild-Life Restoration” consisting of three visionary conservationists: Thomas Beck (publisher of Collier’s Weekly), Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling, and Aldo Leopold. In about two dozen brilliant pages, the “Beck Commission” identified a series of potential projects to secure an initial five million acres of “submarginal” lands for broad-scale wildlife conservation, including lands purchased through federal “duck stamp proceeds.”

With the aftermath of the stock market crash of 1929, most hope for federal appropriation for this sort of conservation declined, and the stamp-funding issue arose once again. A new U.S. President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was sympathetic to the cause of conservation. (For example, among actions in his first 100 days, in 1933, he created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a program which would be used to build roads, bridges, dams, and impoundments at many refuges.)

At the same time, a bill to establish the stamp was being promoted by Senators Norbeck and Frederic C. Walcott (R-CT). In the House of Representatives, Congressman Richard Kleberg (D-TX) took the lead.

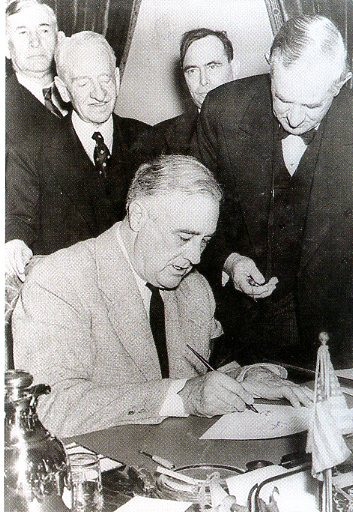

The bill soon passed and was signed into law by FDR on March 16, 1934. With Roosevelt’s signing, the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, popularly known as the Duck Stamp Act, required all waterfowl hunters 16 years of age or older to buy an annual stamp.

The artwork for the first stamp (1934-1935), showing a pair of landing Mallards, was created by Ding Darling in about an hour. The rush was due to a sudden printing deadline. Darling, the Pulitzer-Prize winning American cartoonist and dedicated conservationist, had just recently been appointed the Chief of the Bureau of Biological Survey by FDR.

The revenue generated from the stamp was directed to the Department of the Agriculture. Five years later, the authority was transferred to the Department of the Interior and the new U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to buy or lease wetland habitat.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Now, 80 years later, we can review the use of stamp funds, currently close to $900 million, and we can visit the wetland, riparian, and grassland habitats in the National Wildlife Refuge System that have been secured through the official decisions of the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission. Waterfowl, other birds and wildlife, and the American public have all benefited greatly from the Stamp, and we can certainly celebrate that fact after these 80 years.